15 Mar 2018

WHO launches health review after microplastics found in 90% of bottled water

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has announced a review into the potential risks of plastic in drinking water after a new analysis of some of the world’s most popular bottled water brands found that more than 90% contained tiny pieces of plastic.

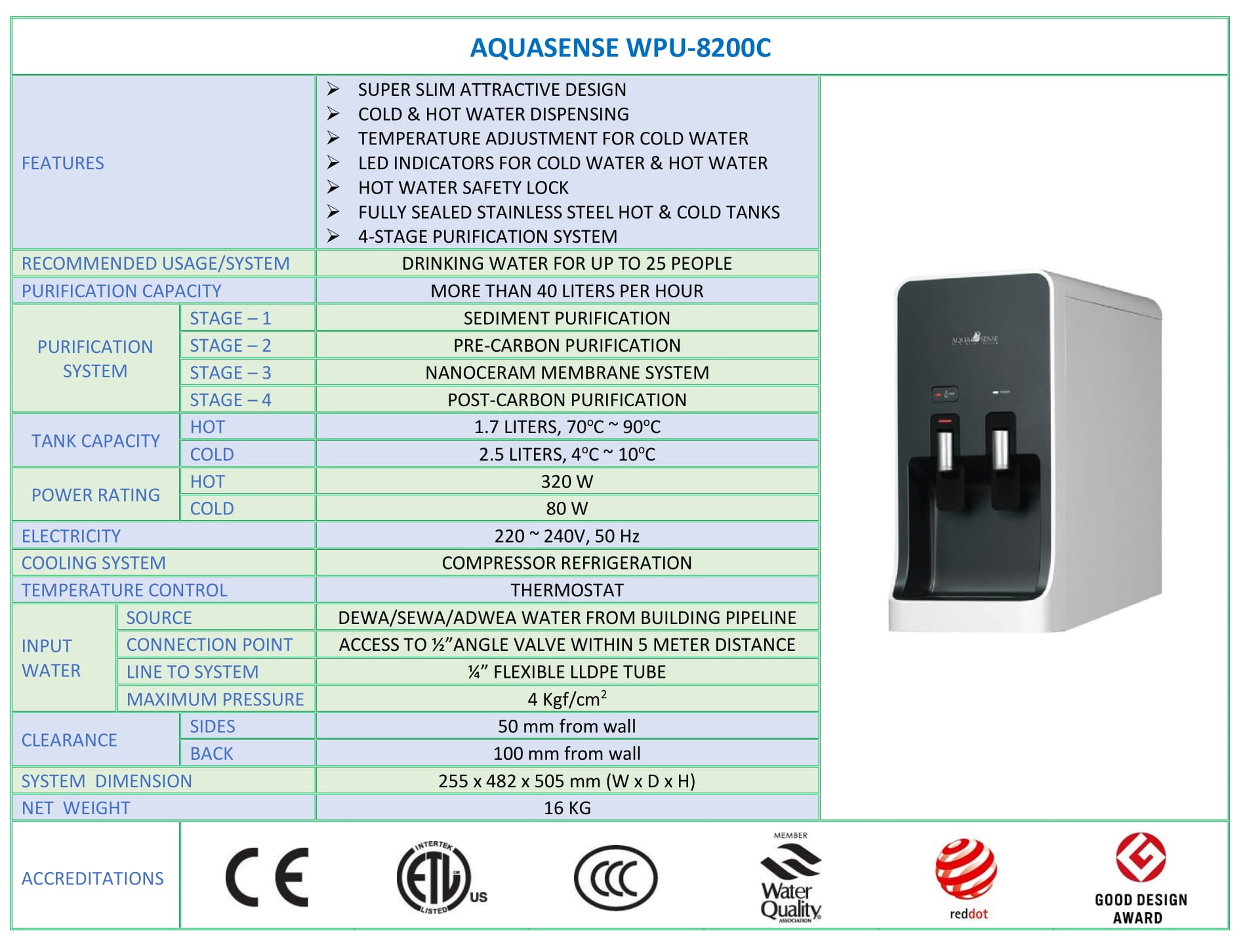

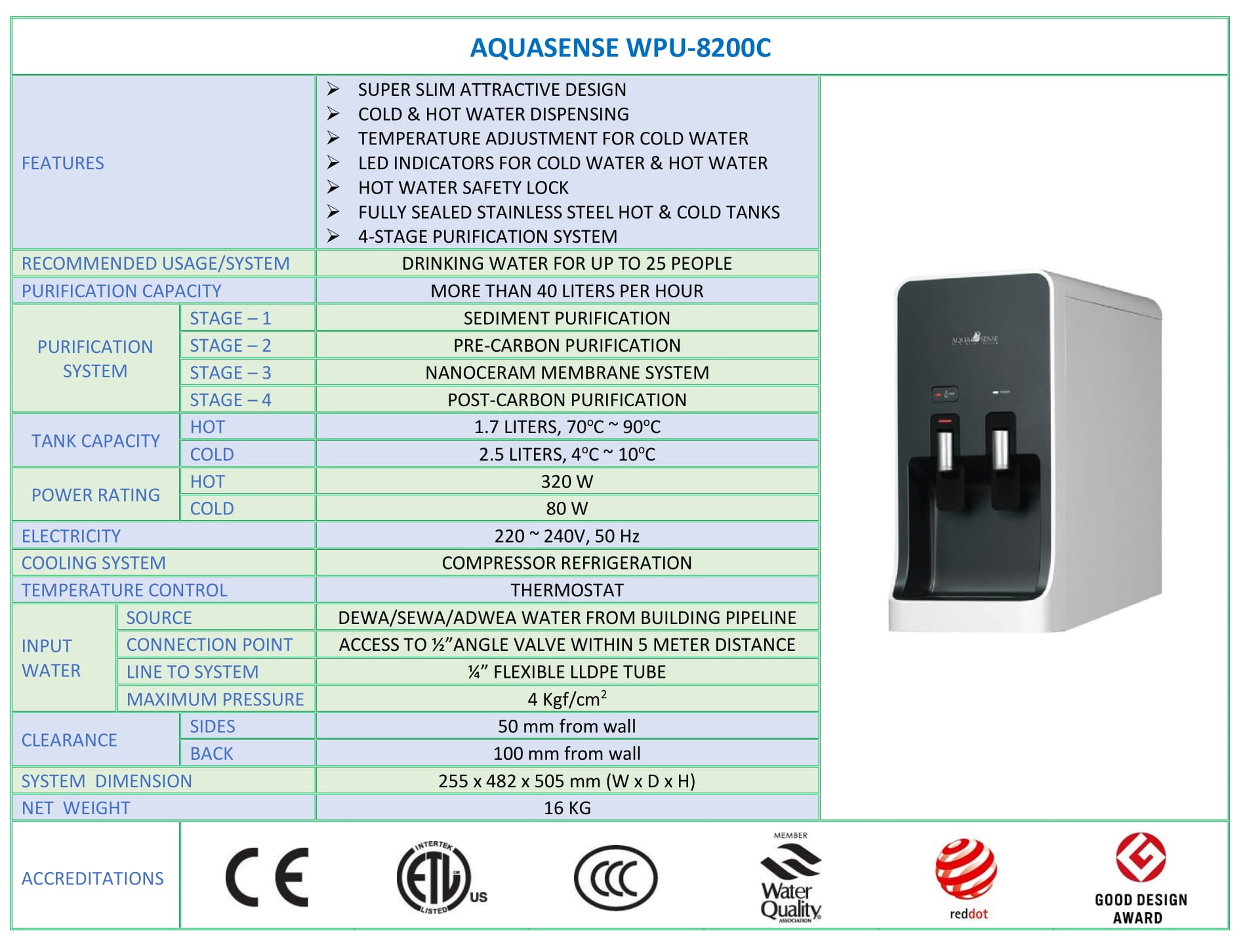

In the new study, analysis of 259 bottles from 19 locations in nine countries across 11 different brands found an average of 325 plastic particles for every litre of water being sold.

Story at-a-glance

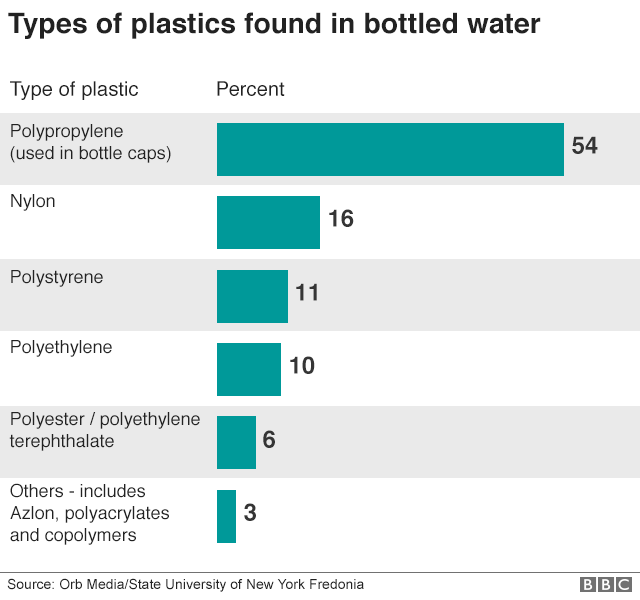

Tests reveal bottled water contains nearly twice as many microplastic particles per liter as tap water. The contamination is thought to originate from the manufacturing process of the bottles and caps

Researchers tested 259 bottles of 11 popular bottled water brands for the presence of microscopic plastic. On average, the bottled water tested contained 325 pieces of microplastic per liter

Only 17 of 259 bottles were found to be free of microplastic particles, and none of the brands tested consistently free of plastic contaminants. The worst offender was Nestlé Pure Life, the most contaminated sample of which contained 10,390 particles per liter

In response to these findings, the World Health Organization has vowed to launch a safety review to assess the potential short- and long-term health risks of consuming microplastic in water

A report by the U.K. Government Office for Science warns plastic debris littering the world’s oceans — 70 percent of which does not biodegrade — is likely to triple by 2025 unless radical steps are taken to curb pollution

World Health Organization Launches Health Review

In response to Orb Media’s report, the World Health Organization (WHO) has vowed to launch a safety review to assess the potential short- and long-term health risks of consuming microplastic in water. WHO’s global water and sanitation coordinator, Bruce Gordon:

“When we think about the composition of the plastic, whether there might be toxins in it, to what extent they might carry harmful constituents, what actually the particles might do in the body — there’s just not the research there to tell us.

We normally have a ‘safe’ limit but to have a safe limit, to define that, we need to understand if these things are dangerous, and if they occur in water at concentrations that are dangerous. The public are obviously going to be concerned about whether this is going to make them sick in the short term and the long-term.”